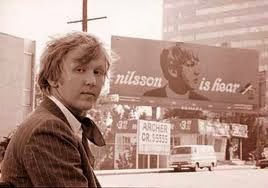

HARRY NILSSON: 'FLASH HARRY' (Originally

released in 1980; reissued by Varese Sarabande, 2013)

It's about time, isn't it? Time and

distance provide perspective. And it's about time time was afforded to this

strange misfit record. In the context of its debut release date - when Adam

& The Ants, Siouxsie & The Banshees, Public Image Limited, Gang Of Four

and The Jam were filling the music press weeklies (yes, Pop was weekly then),

and rap was emerging with The Sugarhill Gang - 'Flash Harry' must have

seemed like the fat boy at the schoolkids' party, the outsider who - whilst

everyone else was snogging or dancing or getting drunk and having the greatest

time because it was (most probably) the first time (and it's all about time,

isn't it?) - stood in the darkest corner with a plate of Wotsits in one hand

and a glass of warm Tizer (into which a passer-by has deposited a cigarette) in

the other. Sidelined, ignored. Who needed a record of an ageing MOR singer with

his all-star band and expensive studios and songs about - about - about nothing,

really? In the eye of the glowing fireball of 1980 pop there was Talking Heads

asking where we could find ourselves, Mark E. Smith of The Fall telling us how

he wrote 'Elastic Man', Elvis Costello crying that the riot act

be read, Chrissie Hynde of The Pretenders ordering us to leave her out of our private

life drama, and Joy Division pleading for us not to walk away in silence.

This was urgent, essential and vibrant stuff, compared to which Harry Nilsson's

silly seemingly-insignificant songs about making lemonade or the rain falling

are beyond light-headed. Empty-headed could be nearer the mark.

Even if one were a fan of Nilsson, or even someone cognisant of his past

track record - and if you don't know, then you are advised to seek out and

enjoy the 'RCA Albums Collection (1967-1977)' box which was also

released in 2013; seventeen discs of ten years' worth of mostly great music,

retailing for a mere £40 (if that); come on, The Who are charging over £80 for

their measly four disc 'Tommy' reissue. Hang on, where was I? Oh yes; if

you knew Nilsson's other records - you would be scratching your napper,

wondering what had happened to his talent for song craft. Nilsson's gifts were

peculiar and particular; he was a master of melodic minimalism, forging songs

from the simplest musical forms. 'One' barely deviates from a single

note, 'Coconut' is played on a single chord. His bare-bones approach is

there at its purest in the piano demos included on the RCA box; often, it seems

as though he's singing different lyrics over the same riff. He treated

songwriting as exercises in structure. The differences occurred in the

arrangements, the instrumental colourings, the lyrical attitudes adopted. He

was a chameleon but his most identifiable talent was in making the saddest

'happy' songs and the happiest 'sad' songs. He had no time for the intricate

brow-furrowing virtuoso complexities of a Zappa or the stylistic adherence to a

narrow soundscape like My Bloody Valentine. A child could play a Nilsson tune

on a piano with one finger and pretty much capture its essence. But the

question would be, "Would a child want to play any of the songs on

'Flash Harry'?" Because these numbers have none of the old lyrical

hallmarks of Nilsson (he was a short story teller, a master of the vignette).

A

glance at the songwriting credits signals that, creatively, the well must have

been running dry for Harry. Of the ten songs, two are written by Eric Idle,

another two are cover versions, five are by Nilsson in collaboration (the one

written with John Lennon, 'Old Dirt Road', first appeared six years

earlier), leaving only one solo Nilsson composition. In 1977 he composed all ten

songs on his final RCA album, the sublime masterpiece 'Knnillssonn'.

What had he been doing for the intervening three years? What's he playing at?

What he certainly was not playing was catch-up with modern Pop. Lindsay

Buckingham was determined to make Fleetwood Mac more dynamic and edgy and

experimental, and 1980 saw the double-album commercial suicide note 'Tusk'

hit the record racks to the general bewilderment of Mac fans (who knew what

they wanted - more of the same, thank you - and they didn't want that).

Ray Davies finally dumped the rock operas and returned to short, snappy comic

pop songs, albeit audibly neutered for the American radio stations. Even The

Rolling Stones tried to 'punk up' their act, although, by the sound of efforts

like 'Where The Boys Go', the only Punk record they had ever heard was

Sham 69's 'Hurry Up, Harry'.

Thirty-three years on, 'Flash Harry' finally begins to make

sense. This wasn't an attempt to recapture former glories, or to consolidate a

new fan base by adopting a 'New Wave' attitude or sound. Instead, this was a

strange new step into some hybrid form of ambient Pop. Listening to 'How

Long Can Disco On?' where Harry sleepily croons over a loping white reggae

skank - with the snare drum beats matched by blasts on a fire extinguisher (was

this some oddball salute to his late hotel-and-drum-destroying pal Keith Moon?)

- it's striking how little happens (lyrically, it's almost haiku), rhythmically

or melodically, but how much it stays in the mind. Days later, you may find

yourself semi-singing "D.J… he play… reggae". And this strange

after-effect I find occurring with numbers that (in a sensible, proper world)

don't add up. 'Best Move' and 'It's So Easy' are so inoffensive

and light and pleasant and apparently forgettable, it's bizarre that they

should make any impression. Why should they? They are not about anything, they

have no immediate hook or arresting riff, so why should they take precedence in

the jukebox of my mind over Truly Important New Songs by the likes of Savages,

Lorde and Kurt Vile? Conversely, the one story song, 'I've Got It!',

about having the horn for a prostitute (only to find that she is a he and he

has the horn too), is lyrically complex and difficult to follow. This isn't

helped by Harry sounding heavily refreshed. Notoriously, he decided in the

mid-70s to make the recording sessions a party and had alcoholic bars installed

in the studio, with the tab picked up by RCA. The recent documentary, 'Who

Is Harry Nilsson (And Why Is Everybody Talking About Him)?', was

ghost-narrated by Nilsson from a series of taped interviews and it's quite

alarming, even in this jaded age, to hear how smashed and slurred his voice is.

And a point to consider when thinking about Harry's music is the effects, side

and full-on and after, the laughing juice had on his creative impulses and the

results. The closer on 1976's '…That's The Way It Is' is a

calypso-cum-collapso ditty called 'Zombie Jamboree' where Harry is

barely coherent through an enthusiastic burst of turps-nudging. Stuffed shirts

may bemoan the fall from grace, that the man who soared such heights with his

performance of 'Without You' should now be publicly disgraced, caught

burbling face-down in a puke-strewn gutter. Yes, well, that is a moot point,

but my painter friend Donald made the astute and correct observation that 'Zombie

Jamboree' sounds like a Joe Strummer-sung track from The Clash's 'Sandinista!'

For reasons that have never fully been explained - which is good,

because it means that we have something to talk about - Nilsson never performed

a live show (apart from the occasional guest appearance on someone else's

stage), never toured, never asked people to pay for a ticket to see him. We can

all theorise as to the whys and wherefores. Fear (in some form) has something

to do with it. Purity is another (having attained the best performances and

sound possible on record, why ruin it by playing cavernous, echoey halls with

rotten acoustics, terrible lighting and so on?). Also at work here is the

belief that Pop is a young person's game and, at 39 (when 'Flash Harry'

popped out), he might have felt that it was time to withdraw out of the

limelight with some semblance of dignity. In fact, this was his final release -

his last years before his death in 1994 were devoted to failed stabs at film

production, and a small business concerning audio cassette books (including

Graham Chapman's 'A Liar's Autobiography') - but, even here, he

sometimes, somehow, seems to be barely present. An alternative title for the

album could have been a play on the hit Peter Sellers film at the time, 'Being

There' - 'Almost There', perhaps, or 'Not Being Here'. He appears and then

disappears in a 'Flash' from the material. He's not even on the opening song!

It's almost as though Nilsson has wilfully undermined himself by handing his

producer's reins over to Steve Cropper, used the songwriting skills of others

(the most Nilssonesque song in terms of subject matter and melodic construct is

his bouncy cover of 'Always Look On The Bright Side Of Life' from the

Monty Python film 'Life Of Brian'). It's as though he's passing the

baton on to others and, with a tip of the titfer, saying, "I'm off, chaps.

Thanks for the ride."

Such is the nature of Art, it's often the case that the less there is in

the artwork (a Rothko painting, or a minimalist composition), the more one can

see or hear in it. The reverse is certainly true with Bob Dylan who, even at

this late stage in the game, confuses quantity for quality and will happily

trot out 10 minute songs that have absolutely nothing worth hearing. And though

'Flash Harry' is neither the most representative or the best (whatever

that means) Nilsson collection, it throws up - sorry to use that expression - a

whole raft of questions about Pop music (its possibilities, its highways and

byways, where it can go, where it mustn't, Pop as mode of personal expression,

the depths and shallows). It is, in its own small, modest way, a brave work. It

dares to be silly (when music became intensely serious) and to be bland (when

Pop's very nature is to grab you violently and scream in your face). It may not

be a great work of Art but it's a great work of Life. It's about -

"Time, gentlemen, please!"

Lennon says: "We live in a world where we have to hide to make love, while violence is practised in broad day light."